Drive, Raiders of the Lost Ark, The Dark Night, The Matrix, Jurassic Park, Toy Story 4: What do these movies have in common?

Right! They all start with a prologue. Simply put, a prologue is, as Doug Eboch defines it in a recent post, “an opening sequence which is not critical to the plot.”

Eboch offers an insightful analysis of a prologue’s many functions.

In some movies, the first part of the story lacks drama. Because of the specific nature of a particular story, the initial Act I sequences can’t generate conflict or action. In this case, a prologue could help supply the needed dose of drama to “grab the audience and draw them into the story.”

In other cases, what is missing in Act I’s opening sequences is an indication of what the tone of the movie will be. A prologue could be useful in establishing the tone.

Finally, it could be that the story-world’s rules – the laws governing the arena in which the story takes place – are very specific, different from how the real world works, or that the arena involves technical elements that need to be established or made clear in advance. That’s another purpose a prologue could serve.

Eboch illustrates all of this by examining The Matrix, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and Romancing the Stone.

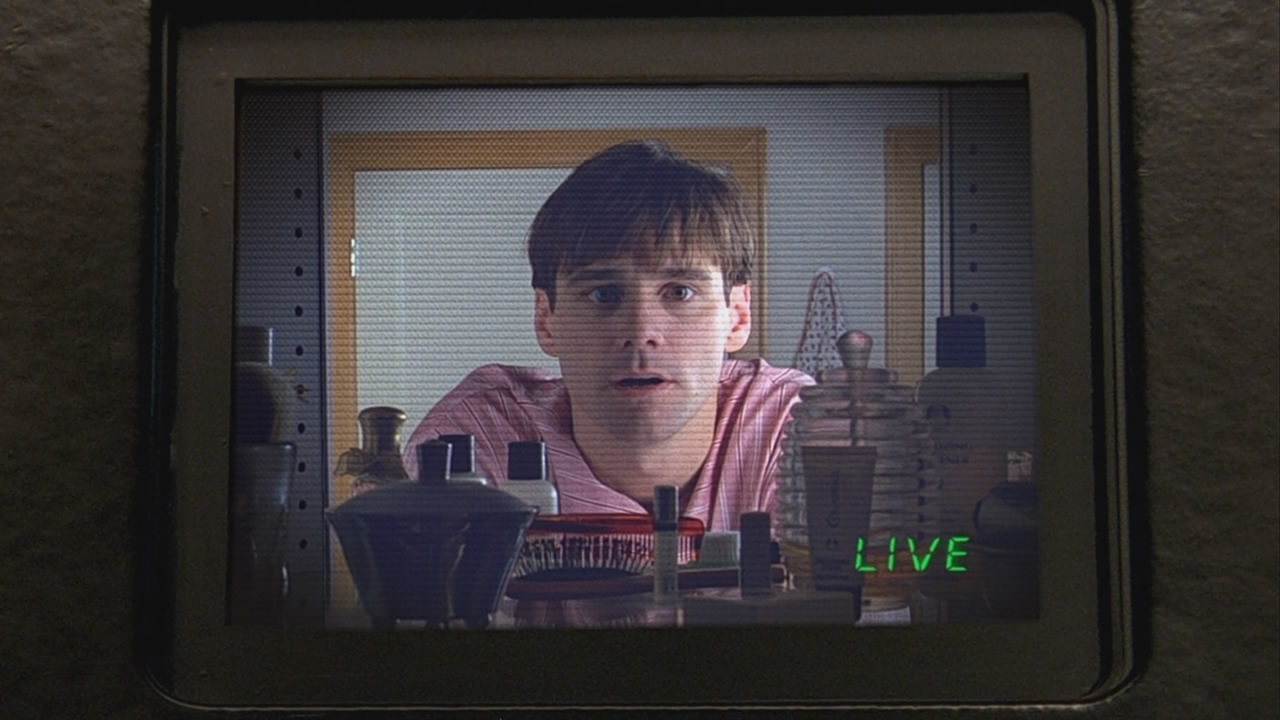

I would like to add here another fine example: the prologue of The Truman Show. Producer Christof (the antagonist) and his main actors (the antagonist’s allies) address the audience directly, hyping the greatness of their program, while Truman, unaware that he is the central character in a 24-hour-a-day reality show, performs a monologue in front of his bathroom mirror; looking at himself (and at us), he gives voice to his private dream of adventure and freedom, oblivious to the camera filming him from behind the glass.

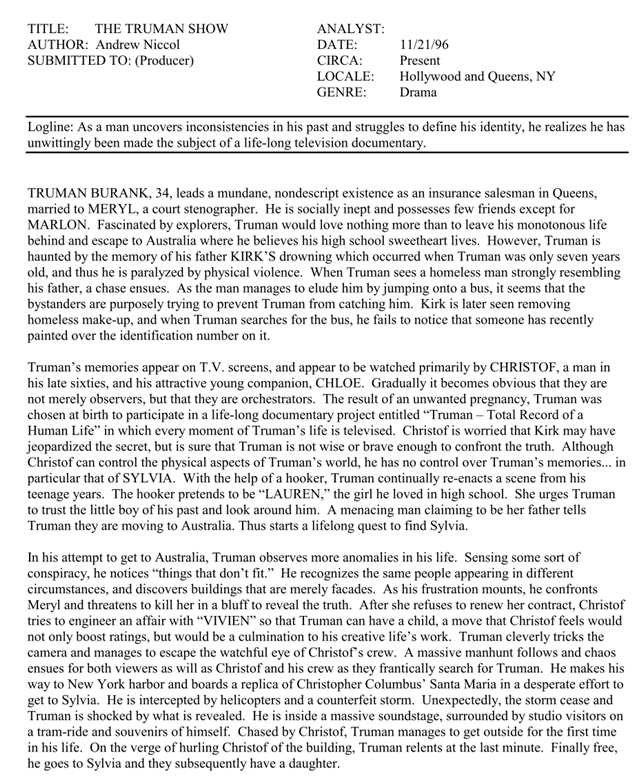

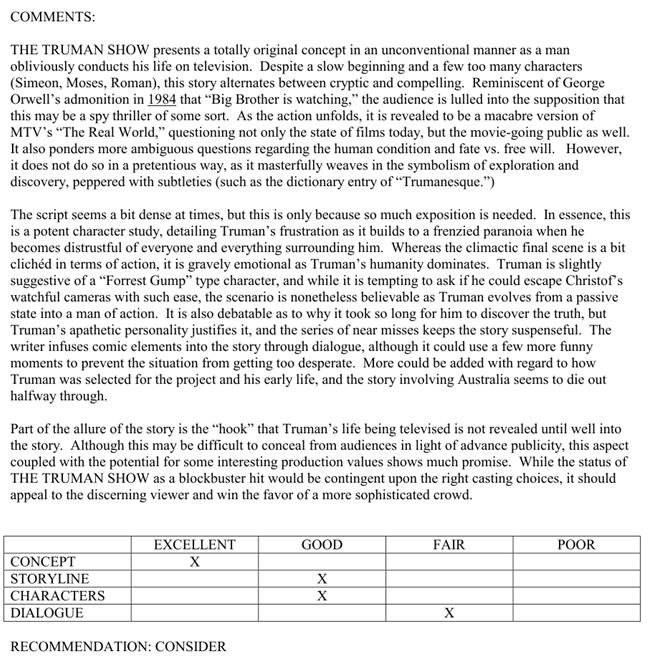

In the drafts of the script circulating on the Internet, the prologue is absent. Evidently, director Peter Weir, the main responsible for the development of the original story written by Andrew Niccol, decided at some later point in the process that this prologue was necessary. Why?

Well, for most of Act I Truman is mainly passive. His behavior is affectedly conformist and almost disturbingly naïve. Having the viewer know from the beginning that he is the innocent victim of a huge reality show makes it much easier to relate to the character. The prologue makes his drama clear from the very beginning, whereas Niccol’s first draft of the script delays the viewer’s discovery of the truth till much later in the story.

Thanks to the prologue, we also know the rules of the game. Not only is Truman bereft of privacy because of ubiquitous hidden cameras, but the weirdly fake and consumerist atmosphere of Seaheaven is precisely the consequence of the town being a TV set. It is a place where products and an entire lifestyle are promoted – thus the prologue conditions us to immediately grasp the movie’s satirical intent.

Finally, the protagonist is played by Jim Carrey, whose presence could have tilted the film’s tone into the strictly comedic. Despite the movie’s many funny moments, however, its emotional core is a dramatic one. And this is precisely the tone anticipated in the prologue, where crucial thematic elements are established (Christof saying that “there is nothing fake about Truman himself,” for example; and the story imagined by Truman in front of the bathroom mirror is openly about life and death: “If I die before I reach the summit, you’ll use me as an alternative source of food”).

To fully appreciate the importance of this prologue (and of the entire development that Niccol’s script underwent) have a look at the coverage of the first draft. I’ve copied the document here below. It’s been out on the Internet for a while, but is still worth reading:

Be First to Comment