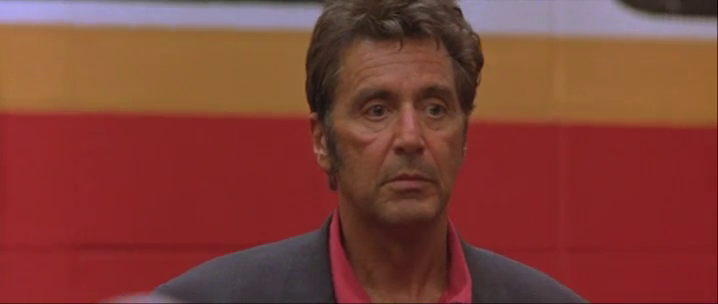

“I don’t know what to say really”. The legendary Any Given Sunday speech, the ultra-famous pep talk given by coach Tony D’Amato to his team before a crucial match, begins in a way you wouldn’t expect. I have just noticed it while watching the scene one more time (the umpteenth time: it’s always a pleasure). Considering the power of the performance that immediately follows, this first line of understatement – a seemingly disheartened captatio – has an ironic aftertaste. But that’s what screenwriting is about: misleading audience’s expectations to prepare a twist.

A few notes on this marvelous piece of writing (and acting, of course):

1. Speechwriting is storytelling

The scene tells the story of a man who regains his will and shares it with his men. It is because D’Amato changes through the speech that his players change in the same way, finally being inspired.

2. The story can be broken into Acts

Act One:

The realization of being “in hell” is an Inciting Incident. An inner debate (to fight or not to fight) follows. Then, the choice to go for the mission, which is in turn essentially a quest to find the motivation he originally lacked (“I am too old”, says D’Amato).

A short Act Two:

The journey in search of motivation starts. It is a confessio that the players don’t expect. D’Amato looks back into his past, only to admit that it consists of a chain of failures. At the end of the chain is the worst point: his statement that life is about things being taken away from you. So, not a whiff of motivation. All is lost. Until… a different point of view makes its way into D’Amato’s self-examination. At the very end of the fall, the coach recalls another lesson he learned: both in life and football, inches that can be conquered are all around us. Meaning, it is possible to lose, yes, but it is also always possible to gain ground. So…

Act Three:

Back into the fight. From the new angle, finally Damato can see a motivation (“On this team, we fight for that inch!”). He has found it. Since he is part of a group, his men, who have followed him along his journey, must also see it. Now, the final action is waiting to be faced. What still must be done to exit hell, and win: the real fight, the match. The apex of the speech anticipates the story’s climax, underlining the two beats that are essential to it: the self-revelation (the players’s inner need of being part of a team where each one is willing to sacrifice for the others is the key to victory) and moral choice (“whattaya gonna do?”).

3. Frankness to prepare the positive shock

It is through a crescendo of frankness that D’Amato locks the audience onto his feelings and eventually motivates them. First, he admits the group is in an awful situation (no euphemisms). Then, more sincerely: he explains a possible solution, the only possible one (“Either we heal as a team or we are going to crumble”), but it’s not enough since they need motivation. Then, even more sincerely: he has failed as a human being. But with the same sincerity he states with sudden vigor: “On this team we fight for those inches”.

4. Pronouns as keywords

The speech is dotted with keywords. There are the obvious remarks (“inches”, “life”, “hell”…). Perhaps less obvious is the use of pronouns as keywords to mark the flow of energy between coach and players (I, we, I, you, I, I, I, WE, WE, You…).

There are many good rhetorical analyses of this scene out there in the Internet. I hope mine contributes as well to the appreciation of this piece of art. For sure, every time one watches it, the impact is strong. Like the moment of the characters in the locker room, for instance. Here is how John Logan and Oliver Stone describe it in the screenplay, at the end of the speech:

Be First to Comment