My favorite moment in The Big Short is when Mark Baum (Steve Carell) forces Georgia, a Standard & Poor’s analyst, to admit that the agency has been assigning its clients false positive ratings, fearing that otherwise they would have gone to Moody’s, their rival firm.

The scene is funny: the analyst wearing eye exam sunshades is an ingenious gag – the childish cruelty of the allusion (the blind controller…) is appropriate.

The scene is also interesting from a broader screenwriting perspective. The end of the dialogue between Mark and Georgia directly addresses a tricky issue screenwriters Charles Randolph and Adam McKay had to tackle throughout the whole script: the moral consistency of their characters.

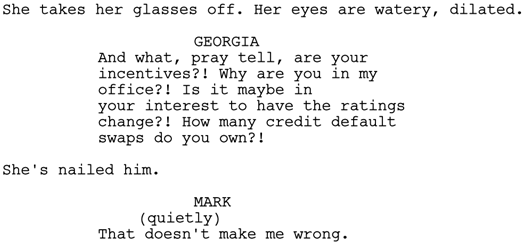

Here is how Georgia reacts angrily to Marks charges:

Which provokes the climax: Georgia’s line touches a raw nerve…

![]()

The fund managers who discover the rottenness behind the mortgage derivatives market and its fragility, who invest betting against the system and win – gaining tons of money while triggering the 2007 financial crises – aren’t like Robin Hood. They are part of the system and they profit by its weakness to make money, not to help poor people (actually, giving start to the crises, their action makes a lot of people become poor).

Discussing the movie on an insightful (as usual) episode of Scriptnotes, John August, Aline Brosh Mckenna and Rawson Marshall Thurber highlight the skill of the writers in keeping the viewers rooting for the characters despite the ambivalence of their goal.

They make a good point highlighting how much the script counts on putting into the foreground the negativeness of the antagonist – the fraudulent bankers. Irritated by this, viewers are less inclined to care about the inconsistency of the protagonists. These, furthermore, are all depicted as underdogs.

Another good point is stressing the importance of Ben Rickert (Brad Pitt’s character). It is especially important the scene where Ben reminds Charlie and Jamie – the two young investors he is helping – the huge social costs of their bet: they shouldn’t be happy. The conscience of the consequences and the sadness generally shown by characters in the movie is indeed another important element – see for example the scene where the two Baum’s managers visit the man who will lose his house.

So, yes… watching the movie a second time, you will notice how much the writers were concerned with this issue.

For example, addressing directly the problem of coherence – making the audience conscious that the story is aware of it (the line by Georgia quoted above; the reprimand by Ben) – is another way to keep the viewers engaged with characters. It is a way to feed the viewers’ trust. Think of the admission of trader Jared Vennett (Ryan Gosling) who, declaring his satisfaction for the huge sum he has won (he is the only one to show his happiness), admits he is not the hero of the story.

Not less important is the suggestion that, if other less profitable ways to face the scandal were possible, the protagonists would have taken them. At one point, Charlie and Jamie go to The Wall Street Journal to denounce the banks, but the journalist isn’t courageous enough to write a piece about it.

There are also many other little things. For example, when Michael Burry (Christian Bale) prevents his clients from abandoning the bet, he writes them an email to tell them that he is doing it to protect them from the fraudulent market. He is not acting exclusively out of his own interest…

Perhaps, the most powerful solution in order to preserve the favor of the audience is Baum’s storyline, the strongest one in the movie. We learn his back-story. We know his brother killed himself. Since then, Mark thinks that the system is a lie. His bet becomes a way to fight what caused his brother’s death (the man had been screwed up) and to get through his sense of guilt (Baum didn’t listen to his brother, he didn’t felt how desperate the man was in his soul, and now regrets of having just offered him some money, not love). So we know Mark doesn’t care about money. He appears to have pure intentions. To the point that, near the end, he is willing to afford the risk of losing the bet because, waiting to sell his swaps, he will cause the banks a bigger damage “We’re going to shove the knife in to the hilt…”).

Sometimes it doesn’t matter what you do.

It’s more important why you do it.

Most of all, how you tell it…

Be First to Comment