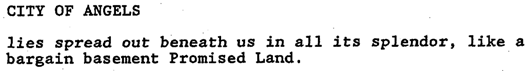

We are taught “show, don’t tell”. But… there are exceptions to every rule. Take for example these lines of description. They are at the very beginning of the script. The author introduces the city (Los Angeles) where the story will take place and he depicts the view on the metropolis:

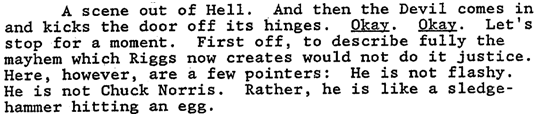

Take also these other lines, from a later page of the same script, depitcting the surprising entrance of the hero in a room crowded with villains:

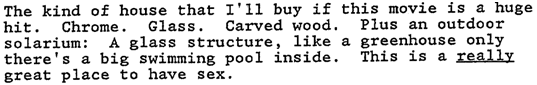

Now, same script, one last example, very famous, depicting the place where the drug dealers live:

A “bargain basement promised Land”!? How do you film it?

“Let’s stop for a moment”!? Wasn’t characters’ action the only one to be relevant in a script?

“If this movie is a huge hit”!? Robert McKee would raise an eyebrow, disapproving.

Yet the three quotations come from an unforgettable, successful script (Lethal Weapon, as you have probably already realized), by Shane Black, whose peculiar style they perfectly exemplify. Comments, jokes, metaphors (“Shane Blackisms”)… in other words: narration.

Screenwriting manuals are unanimously against it. The most severe criticism I have ever read to the use of narration in a screenplay, though, is in a Los Angeles Times article by the great dramatist and screenwriter David Mamet: “It’s monstrous”.

Mamet is motivated by the fact that in late Eighties and early Ninenties this kind of writing was widespread and fashionable (Lethal Wapon script had been seminal).

Mamet’s diagnosis is right. Narration is used to please readers, those people in the industry who are in charge of reading tons of scripts, to write coverages, and to recommend the screenplays that deserve to be bought.

Put yourself in a reader’s shoes. At the end of the day you’ve read hundreds of pages, good material has been rare, you are tired, your attention is vanishing, you pick up your last script before leaving the office and… What the hell, “a bargain basement Promised Land”?! I had never read something like this! “Okay. Okay. Let’s stop for a moment…”?! Hey, this guy is provoking me! “The kind of house…” and he is funny too…

You will certainly remember that script. It is full of candies for you, the reader. You have noticed it and the script has more chances of being recommended for further consideration and, perhaps, for being bought.

Mamet is also right (like manuals are) in defending the rule: screenwriters should restrict themselves to “delineating what the actor does, and what the camera shoots”. In a screenplay, drama is king.

Having said this, to me his blame is excessive. In many good and produced scripts you’ll find bits of narration. Never in a Shane Black script proportion, but, still, here and there, accurately weighed, in tune with the genre (jokes are okay in an action movie, not as much in a psychological drama) you will hear the voice of the author who reveals himself commenting the action.

The fact is narration is pleasurable and, used with shrewdness, it helps to sell a script. It enhances the impression that the writer is… a writer: someone with talent, creativity, imagination.

So, “show and tell” is accectable? The rule of thumb should be the following. Use it in a spec script (Lethal Weapon was sold on spec), when grabbing the attention is essential in order to make your story recognizable among many others. Use it less, or avoid it at all, in a commissioned screenplay, or in further drafts along the development process, when executives/producer/actors/director are already convinced by your story and like it.

Be First to Comment