Room, Jackie, Brooklyn, Star Wars: The Force Awakens, Rogue One, The Crown…

So many stories recently with female protagonists. Now the question becomes: Is there a specific structure for films or TV series featuring not a hero but a heroine? In other words, is the craft of screenwriting – its techniques – prepared for the task in a decade where the diversity issue has grown hot?

If you want my humble answer: yes. Yet in academia – and perhaps slightly less so in the industry – the issue is debated. The screenwriting tool under scrutiny is the Joseph Campbell/Chris Vogler narrative pattern: the so-called monomyth, the legendary hero’s journey.

According to those who criticize it from a female perspective, since the model comes from myth studies in which the protagonist is a warrior, the model is tainted by a subtle bias, and is therefore unsuitable for creating stories that feature well-expressed female mindsets and sensibilities. Too much aggressiveness and desire for reward, we’re told, too much emphasis on bravery; too few choices usually faced by women (whether to have a child, for example), little to no attention given to protective motivations, and no connection with the deep emotional self.

John Truby, reviewing Inside Out, has some interesting observations on the topic.

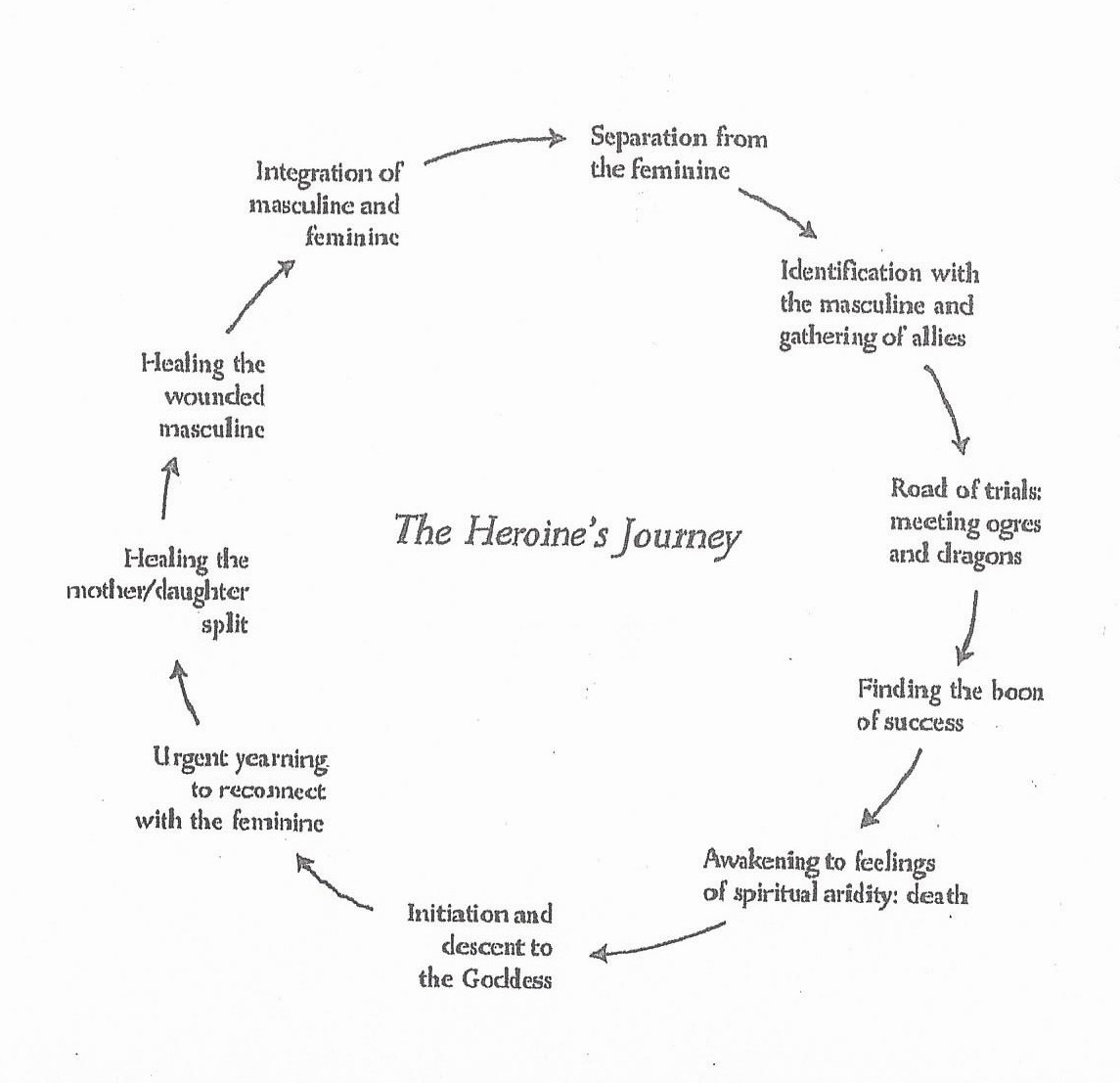

A possible solution to the problem – the basis for an alternative, female approach to drama – is the narrative framework elaborated by Maureen Murdock in her book, The Heroine’s Journey. Murdock, a psychotherapist formed under Campell’s guidance, has conceived a version of the monomyth depicting a journey of rediscovery of femininity within a world dominated by male codes.

If you are interested in the topic and want to learn more about Murdock’s narrative tool, here you will find a useful exemplification of the model, applied by Alla Zaykova in breaking down the structure of Pixar’s Brave.

Even if well done, the analysis leaves me with two concerns.

First. I could easily make an analysis of the same film using the hero’s journey model, and it would work just as well. So is structure really the crucial point, or rather the contents you put into it?

Second. Isn’t femininity as defined in the heroine’s model too much in contraposition to male values and motivations, and thus still – perhaps paradoxically – dependent on them? Wouldn’t it be better to focus directly on what is specific to, and beautiful in, femininity?

Be First to Comment